Tags

1960s cinema, Alfred Hitchcock, Bernard Hermann, Hitchcock, horror, Jessica Tandy, Rod Taylor, Tippi Hedren, Veronica Cartwright

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film The Birds is more than suspenseful horror. It is an exposition of the complexity and conflicting nature of human relationships as they are impacted by outside threats. Hitchcock’s films are laden with binaries, such as good and evil, the ordinary and the extraordinary, lustfulness and chastity, childhood and adulthood, and order and chaos. The Birds is Hitchcock’s ultimate statement of order and chaos.

As analyzed by authors Camille Paglia, Robin Wood, and Richard Allen, The Birds is a fascinating film because it can be interpreted in many ways. Beneath the film’s surface about birds terrorizing a seaside town is a critique of the American nuclear family. Humans categorize and impose order on chaotic nature, which cannot be tamed nor controlled. In the film, the nuclear family represents that imposed order. Its instability reveals humankind’s vulnerability in a chaotic world.

The Brenner family, representing the American nuclear family, is coming apart as a result of Lydia’s unrealistic expectations for her son, Mitch. Lydia selfishly does not want Mitch to marry and abandon her. Mitch, in effect, has become a substitute for her dead husband and his father. The arrival of Melanie Daniels, denoting dangerous female sexuality, must restore order to the Brenner family by making it a reproductive unit again. In his essay, “Avian metaphor in The Birds,” Richard Allen argues that Melanie perpetrates therapeutic change in the Brenner family: “Lydia’s problem is that she has a distorted relationship with her children that renders her incapable of the kind of love that allows her to let them go. In the psychotherapeutic narrative of the film, it is Melanie’s task to conquer Lydia’s fear of abandonment by offering the kind of unconditional love that will release Lydia from this fear and, at the same time, liberate Mitch to become her mate” (Allen 285). Melanie has the potential to restore order to the Brenner family, which has been missing ever since the death of Lydia’s husband. Melanie’s other role in the film is that of a martyr. She is the victim to several bird attacks, testing her physically, emotionally, and mentally.

Many commentators have tried to answer the following questions about The Birds. 1) Why birds? 2) Why do they attack? I have never accepted an explanation for the bird attacks for the simple reason that it is unnecessary. I agree with author Robin Wood’s assertion that the birds and their actions cannot be explained and are merely an agent of chaos whose purpose is to disturb humanity’s imposed order. In many ways, the birds are Hitchcock’s ultimate McGuffin. Hitchcock defined a McGuffin as “The plot device of little intrinsic interest, such as lost or stolen papers, that triggers the action” (Truffaut 123). Having concluded that the answers to these two questions regarding the birds are irrelevant or insignificant, we consider the binaries Hitchcock uses in the film.

Sexual repression

One of the film’s opposing binaries is lustfulness and chastity. The film is full of sexual repression and tension, an energy that is released in the form of bird attacks. Lydia is not comfortable with the idea of Mitch being with another woman.Mitch has become a surrogate husband to Lydia and a surrogate father to his sister, Cathy. However, like the birds themselves, the humans in the film are retreating to their own animalistic behavior. Mitch and Melanie, the human equivalent of the lovebirds, are sexually attracted to each other. Hitchcock makes sure that the women in Bodega Bay are not sexualized like Melanie, amplifying her threatening presence.

The sacrificial lamb

Throughout his career, Hitchcock depicted icy blonds who represented dangerous female sexuality. In her book on The Birds, controversial feminist Camille Paglia argues: “In this film, as in so many others, Hitchcock finds woman captivating but dangerous. She allures by nature, but she is chief artificer in civilization, a magic fabricator of persona whose very smile is an arc of deception” (Paglia 7). Melanie’s presence is threatening to Lydia who fears abandonment and loneliness. Therefore, Melanie becomes the sacrificial lamb in a film laden with religious symbols. In an interview with French film director, Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock called Melanie a “wealthy, shallow playgirl” (Truffaut 154). In a private conversation with Mitch at Cathy’s birthday party,Melanie reveals that she wants more out of her life. The film documents Melanie’s transition from a reckless, childish playgirl to a selfless woman.

The Birds begins in San Francisco. Hitchcock had an extraordinary gift for conveying visual messages to the spectator without the use of dialogue. The introduction of Melanie Daniels shows her artificiality. Someone whistles at Melanie and she smiles. She looks at birds massing overhead before walking inside the pet shop (see fig. 1). Melanie is a beautiful girl who enjoys the attention of men. The birds looming overhead foreshadow the impending doom. The birds will become a vehicle for Melanie’s transformation in the film. In the pet shop, caged birds surround Melanie. Thus begins the cage motif, which will continue throughout the film. Humans become the subjects of metaphorical birdcages, such as the car, the phone booth, the house, and finally, the attic. Fig. 1 Melanie enters the pet shop while Hitchcock exits the building in his trademark cameo appearance.

Fig. 1 Melanie enters the pet shop while Hitchcock exits the building in his trademark cameo appearance.

Lovebirds

The following scene shows Melanie’s absurd quest to give Mitch the lovebirds he wanted for Cathy. After arriving in Bodega Bay, Melanie meets Annie Hayworth, her rival who is still in love with Mitch (see fig. 2). Annie attempted to gain acceptance in the Brenner family unit but was unable to penetrate Lydia’s expectations. Annie realizes Melanie’s interest in Mitch when she sees the lovebirds. The lovebirds symbolize Mitch and Melanie’s love for one another. As Walter Raubicheck and Walter Srebnick suggest in Scripting Hitchcock, the lovebirds serve an important purpose in the film: “Hitchcock insists that the lovebirds are introduced in the film’s first scene because “love is going to survive the whole ordeal.” In fact, Hunter’s final script has Mitch saying at the end: “What do we have to know? We’re all together, we all love each other, we all need each other. What else is there?” (Raubicheck and Srebnick 72). It is unsurprising that the lovebirds seem to be the only birds in the film not intent on creating chaos. These particular birds signal the characters’ relationships to one another. Furthermore, the lovebirds emphasize the importance of having healthy, interpersonal relationships. Fig. 2 Annie watches as Melanie, her rival for Mitch’s affections, drives away.

Fig. 2 Annie watches as Melanie, her rival for Mitch’s affections, drives away.

Order and chaos

The first bird attack occurs when Melanie crosses Bodega Bay on a small boat to meet Mitch on the other side. As she approaches the dock where Mitch stands, her demeanor turns again to that of a spoiled socialite who has taken the sexual upper hand. It is at this moment that Hitchcock chooses to unleash the first bird attack, which is directed at Melanie of course (see fig. 3). It is as if Hitchcock is criticizing female artifice. Melanie’s quest to leave the lovebirds for Mitch’s sister Cathy is absurd. In many ways, civilization and its artificial social constructs blind humanity from the natural world around them and, by extension, mask their vulnerability amidst chaotic nature. Melanie is artificial and represents this paradox. The first bird attack and each of the subsequent attacks disturb humanity’s imposed order and leaves it in chaos. Fig. 3 A close-up reveals Melanie’s glove, which is stained with blood.

Fig. 3 A close-up reveals Melanie’s glove, which is stained with blood.

After the first bird attack, Mitch takes Melanie inside the restaurant to heal her wound. The two continue their playful banter which started in the pet shop. Melanie maintains her artificial demeanor and lies to Mitch, saying that she came to Bodega Bay to meet her friend, Annie Hayworth. Hitchcock employs canted angles in this scene, echoing his expressionistic influences (see fig. 4). The message is clear. Humans and, specifically, the characters in the film are completing their day-to-day rituals even while the world around them begins to descend into chaos. Lydia is introduced in this scene. Her cold demeanor toward Melanie is immediately recognizable. Mitch invites Melanie for dinner that night. Fig. 4 A canted angle shows Mitch tending to Melanie’s wound.

Fig. 4 A canted angle shows Mitch tending to Melanie’s wound.

False security

In the following sequence, Melanie arrives at the Brenner home. Before exiting her Aston Martin, she applies makeup, emphasizing her artifice. Grateful for the lovebirds, Cathy embraces Melanie. Cathy is a child who does not have preconceived notions of Melanie and readily accepts her. This is in contrast to the other characters, who all judge Melanie to some degree. The interior of the Brenner home is darkly lit and poorly decorated (see fig. 5). A portrait of the dead husband and father looms over the mantle, as if his presence still haunts their lives. Later in the scene, Mitch and Lydia converse, revealing their unusual mother-son dynamic. Mitch calls Lydia “darling”, implying his role as substitute husband without the sexual implications. One draws from this sequence the notion that this nuclear family is an unusual one. The sequence ends with Mitch noticing crows massing on the telegraph wires outside. Many of the early sequences present fabricated security whether it is in the form of love, family, or the home. Meanwhile, the birds become an increasingly threatening presence and always seem to be looming over the characters and their actions. Fig. 5 The interior of the Brenner home acts as a metaphorical birdcage.

Fig. 5 The interior of the Brenner home acts as a metaphorical birdcage.

In the following sequence, the first mass attack by the birds occurs at Cathy’s birthday party. Before the attack, Mitch and Melanie converse on a sand dune. In society, everyone wears social masks to some extent. Mitch and Melanie have worn their social masks with one another up to this point. When Mitch tells Melanie that she needs a mother’s love, Melanie removes her mask and reveals that her mother left her when she was just a child and she does not know where she lives. The intonation of Melanie’s voice changes to that of a child, revealing her desire for a mother figure that she never had. When Mitch and Melanie walk down the sand dune, Annie and Lydia disdainfully look at them. Neither character approves of their coupling for their own selfish reasons. Immediately after, the birds begin to attack the children (see fig. 6). The entire film is built around the notion of fabricated security, like the American nuclear family amidst unpredictable chaos: “The destruction of the children’s party by the birds crystallizes for us in a series of superbly realized images-the upsetting of cakes and cartons of fruit squash, and particularly, the bursting of balloons-that awareness of fragility and insecurity that is the basis of the whole film” (Wood 162). The characters never know exactly when the birds will strike. This sense of doomed uncertainty makes the film’s effect more disturbing. Fig. 6 A bird pecks at a helpless child at Cathy’s birthday party.

Fig. 6 A bird pecks at a helpless child at Cathy’s birthday party.

In the following scene, the Brenner family and Melanie prepare for dinner but before they can eat, a mass of birds come flying down the chimney. The birds, agents of chaos, have penetrated the family home and the false sense of security that it represents: “We have grown accustomed to the imposed and impeccable neatness and order of Lydia’s house. The heavy masculine décor shows us how she clings to the past, to the idea of her dead husband, and the determinedly imposed order suggests the importance the house and furniture have for her. Into this décor the birds irrupt: there is no safety from them, no shelter or screen behind which one can find security” (Wood 163). Later, the sheriff dismisses the reality of the situation. Lydia picks up the pieces to her broken home as if holding onto the sense of security that those objects provide for her. The film draws parallels between Lydia and Melanie. The two women look similar (see fig. 7). Furthermore, both women find false security to hide their own insecurities. Melanie finds false security in her lifestyle as a socialite free from life’s irksome obligations; and Lydia, in domesticity and her relationship to Mitch. Melanie recognizes that Lydia is distraught and offers to take Cathy to bed. Melanie becomes a motherly figure, displaying her kindness to the Brenner family.

Fig. 7 Lydia and Melanie’s striking resemblance

Fig. 7 Lydia and Melanie’s striking resemblance

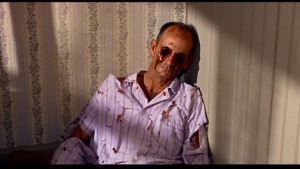

One of the film’s most effective scenes occurs when Lydia discovers Dan Fawcett’s corpse in his house. In this scene, Hitchcock draws parallels between Lydia and Melanie visually in shot composition. The very wide shot of Lydia driving to Dan Fawcett’s farm recalls the very wide shot of Melanie traversing Bodega Bay in a boat. Lydia enters Dan Fawcett’s house and notices the broken teacups, reminding her of her broken home. In several point of view shots, Hitchcock reveals a room in ruins. Hitchcock’s camera shows Dan Fawcett’s corpse and its two pecked out eye sockets pouring blood in two jump cuts (see fig. 8). The shock value of this scene is comparable to that of the shower scene in Psycho. It is made all the more effective by the silence of the house. Lydia, in complete shock, cannot even scream. She rushes out of the house and drives quickly back to her home. Her fast and reckless driving recalls the scene of Melanie’s need for speed in her drive toward Bodega Bay. Fig. 8 Dan Fawcett’s corpse

Fig. 8 Dan Fawcett’s corpse

In the following scene, Melanie and Mitch share a kiss. Wood writes that this tender moment between the film’s hero and heroine is not just another Hollywood cliché: “The moment conveys perfectly the beginning of sincerity in the characters, their acceptance of the human need for a relationship grounded in mutual respect and tenderness. It reveals the essentially positive bent of an undermining and ruthless film: in counterpoint to the breaking down of Lydia, the building up of a fertile relationship” (Wood 165). Melanie and Mitch have dropped their social masks. They are now completely and utterly themselves. Furthermore, Lydia is beginning to accept Melanie, made evident by her thanking Melanie at the end of the scene. Lydia opens up emotionally to Melanie about the loss of her husband and verbalizes her fear of a lonely existence (see fig. 9). Fig. 9 Melanie comforts a fearful Lydia.

Fig. 9 Melanie comforts a fearful Lydia.

The following scene at the schoolhouse is one of the film’s most effective sequences and a display of Hitchcock’s mastery. Melanie sits on a bench outside of the school while crows mass on the jungle gym behind her (see fig. 10). The schoolhouse represents education, another symbol for humanity’s imposed order. However, the schoolhouse is a dark and foreboding place. The bushes outside out of the school are bare. Annie seems to be the only teacher in the school. The stark architecture of the school echoes Annie’s own sexual longing and frustration.  Fig. 10 Crows begin to mass on the jungle gym behind an unsuspecting Melanie.

Fig. 10 Crows begin to mass on the jungle gym behind an unsuspecting Melanie.

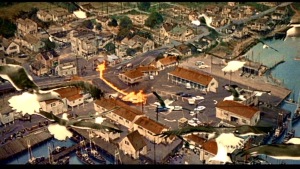

The film shifts to the town where the birds attack the townspeople in one of the film’s most effective sequences. It begins in the diner with an interesting discussion of the bird attacks between Melanie and several townspeople. Melanie moves away from the discussion and looks out the window. She hears a bird’s cry before anyone else. Melanie seems to have an intuition that other characters in the film do not possess. Earlier, Melanie was the first to notice a bird enter the Brenner home from the chimney; and later she hears the fluttering of the birds in the attic. In many ways, children are gifted with an intuitive sense that they lose once when they enter adulthood. Melanie, in many ways, is still a child. She has no obligations in life and is frequently the perpetrator of childish practical jokes. Furthermore, Melanie immediately identifies with Cathy and still longs for the love of the mother that she never had. It is no surprise, then, that Melanie is gifted with an intuition that the other characters do not seem to possess. After Melanie intuitively hears a bird’s cry outside, the attacks begin and engulf Bodega Bay in pure chaos. Fig. 11 In one of the film’s most impressive shots, birds descend into Bodega Bay.

Fig. 11 In one of the film’s most impressive shots, birds descend into Bodega Bay.

Crucifixion

In the end of the film, the Brenner family has become trapped in a metaphorical birdcage where they have the potential to finally become a proper nuclear family unit. Melanie hears birds fluttering in the attic upstairs and decides to investigate the noise without waking the others. Melanie becomes trapped in the room with the birds, which attack her furiously. Birds peck at Melanie’s hands, evoking images of stigmata and crucifixion (see fig. 12). Melanie has become a Christ-like figure who must bring salvation to the Brenner family. Fig. 12 Birds peck at Melanie’s hands.

Fig. 12 Birds peck at Melanie’s hands.

Resurrection

During and immediately following this scene, Melanie undergoes a transformation, or a resurrection of sorts. Lydia is compelled to help the wounded Melanie. Melanie, Mitch, Lydia and Cathy enter the car with the lovebirds, implying that Melanie and Mitch will be able to cement their love for each other. Therapeutic transformation is a common theme in Hitchcock’s body of work and it is ever present in The Birds. The characters in the film undergo transformations, particularly Melanie and Lydia. By the end of the film, Melanie sheds her childish skin and becomes a selfless woman. Lydia, on the other hand, lets go of her control over Mitch and becomes the mother that Melanie never had. Lydia cradles Melanie in her arms, not unlike Mary cradling Christ after his crucifixion (see fig. 13). Melanie looks up at Lydia, who has now let go of her unrealistic expectations for Mitch. At this point, Melanie has become fully accepted into this family unit. Fig. 13 Lydia has finally accepted Melanie and cradles her in her arms.

Fig. 13 Lydia has finally accepted Melanie and cradles her in her arms.

In conclusion, Melanie facilitates the therapeutic cleansing of the Brenner family and makes it a reproductive unit again. In the process, she undergoes her own transformation. The film challenges humanity’s imposed order on chaotic nature and society’s false securities with a series of inexplicable bird attacks. The Birds is not really about birds. Rather, it is an exposition of human relationships and the importance of having them in a world that can be both chaotic and unpredictable.

Annotated Bibliography

Hitchcock, Alfred. Interview by Francois Truffaut. Scott, Helen G., and Francois Truffaut. Hitchcock (Revised Edition). New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985. Truffaut’s interviews with Hitchcock provide a primary source of information for Hitchcock scholars coming from the words of the Master himself. Paglia, Camille. The Birds (BFI Film Classics). British Film Institute, 2008. Print. Paglia, a controversial feminist, analyzes The Birds in terms of its representation of family relations and gender. Paglia’s unique perspective is interesting when scrutinizing the film’s depiction of femininity. Wood, Robin. Hitchcock’s Films Revisited. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. Print. A film historian and respected film critic, Robin Wood offers close readings of Hitchcock’s films. McCombe, John P. “Oh, I See…”: The Birds and the Culmination of Hitchcock’s Hyper-Romantic Vision. Cinema Journal 44 (2005): 64-80. Print. McCombe’s essay analyzes The Birds in the context of literary romanticism and reads the film as a critique of practices that impose a false order on chaotic nature. Raubicheck, Walter and Srebnick, Walter. Scripting Hitchcock. New York: University of Illinois Press, 2011. Print Raubicheck and Srebnick discuss the collaborative efforts of Hitchcock and his screenwriters on three key Hitchcock films: Psycho, The Birds, and Marnie. Allen, Richard. Framing Hitchcock: Selected Essays from the Hitchcock Annual. New York: Wayne State University Press, 2002. Print. In its ten-year history, the Hitchcock Annual was a source of critical discussion of Hitchcock. In one essay, Richard Allen analyzes The Birds.

I remember growing up as a kid and watching “The Birds” for the first time. It was a nail biting experience! This movie gave me a new image of birds in the same way that the movie, “Jaws” made me fearful of sharks.

I enjoyed reading this post. It gave me a whole new perspective on the avian Hitchcock thriller, especially on the heroine – Melanie Daniels.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on SavageFilm.

LikeLike

Danny8991, how can I cite this blog? Do you have a full name?

LikeLike

Danny Savage 🙂

LikeLike